What Is A Dig In Volleyball?(Types, Statistics, Techniques)

Perfectly balancing defense and attack, volleyball relies on the dig as an essential defensive move.

A defensive move in volleyball, referred to as a dig, serves the purpose of preventing the ball from making contact with the ground following the attacking team’s spike or tipping. Alternatively, a dig refers to a situation in which the defending team receives an attacked ball and keeps it in play.

Defining a dig and discerning the distinction between a dig and a pass in the middle of a game is not as straightforward as one might assume.

In the course of this article, What Is A Dig In Volleyball will be explored, the points of confusion will be identified, and the correct technique for digging a ball will be addressed.

What Is A Dig In Volleyball and Isn’t a Dig? (Misconceptions About Digs) and Why Are Digs Useful?

After the attacking team has spiked or tipped the ball into the defending team’s half, a player must resort to a dig.

Useful for two reasons, the dig first prevents the ball from touching the ground, thereby thwarting the attacking team from scoring a point.

Secondly, a skillful dig has the potential to set up a counterattack.

In the context of volleyball, digging emerges as the primary means to prevent the attacking team from scoring, especially when the spiked ball hasn’t been blocked. In such instances, if the ball is on its trajectory toward the back lines, the defensive team must rely on a precise dig to keep it from making contact with the ground.

For utmost accuracy, reference to the NCAA’s rulebook on volleyball statistics will guide our understanding of these essential aspects.

Contrary to popular belief, it’s important to note that a dig is not exclusively awarded in response to an attacking move, such as a spike; defending a tipped ball is also acknowledged as a dig.

Additionally, it is crucial to clarify that the reception of a serve does not qualify as a dig. Despite some sources suggesting that a successful dig includes the reception of the attacking team’s spike, tipping, or serve, this information is incorrect.

To accurately attribute a dig, it is essential to recognize that the award is only warranted when a spiked or tipped ball is successfully defended and passed to another player. The reception of a serve, however, does not meet the criteria for a dig.

Thirdly, it’s important to clarify that a dig resulting from the opposition’s block does not qualify as a dig. For instance, if Team A spikes the ball and Team B successfully blocks it, any subsequent defensive intervention by a player on Team A does not contribute towards a dig.

Furthermore, it is crucial to note that a dig is exclusively awarded in the context of attacking play. Defensive actions following the opposition’s block, even if involving successful ball retrieval, are not categorized as digs.

Lastly, for a play to be acknowledged as a dig, the dug ball must reach a teammate and stay in play. Merely hitting the ball, without preventing a point from being conceded, does not meet the criteria for a dig.

Different Types of Digs

In the realm of volleyball, various types of digs exist, each serving distinct defensive purposes: the regular (traditional) dig, the side dig, the diving dig, and the overhead (overhand) dig.

The regular dig occurs when the defensive player accurately anticipates the direction in which the attacking team will send the ball. Positioned strategically, the player executes a precise dig and proceeds to make a pass to another teammate.

Similar to the regular dig, the side dig differs primarily in hand positioning. In this variant, the ball is directed towards the player’s left or right-hand side, requiring an adjustment in the defensive approach.

Often, the need for a side dig arises when the ball rebounds off an unsuccessful block or when the defensive player misjudges the ball’s original trajectory.

Without the luxury of time for repositioning, the player resorts to hitting the ball from the side, adding an extra layer of difficulty to the dig.

Conversely, the diving dig, commonly referred to as ‘the dive,’ requires the defensive player to throw themselves to the ground to prevent the ball from making contact with it. This scenario typically unfolds when the ball’s speed is too rapid, leaving the player with insufficient time to assume a proper defensive stance.

In the pursuit of effective digs, players typically employ both arms, but a diving player often opts for a quicker one-armed dig.

A unique technique within the diving dig is known as ‘the pancake.’ In this method, a player dives to make a dig, allowing the ball to hit the back of their hand. While considered a last resort, the pancake technique is not frequently utilized in gameplay.

Lastly, the overhead dig, or overhand dig, involves directing the ball above the defending player’s head, as implied by the name.

In this scenario, the defensive player reaches over their head to strike the ball, typically using the heel of the palm.

Dig Statistics

A crucial rule governing dig statistics is clear:

“Team A’s digs CANNOT total more than Team B’s total attacks minus their kills and errors. Those are the ONLY balls that can be dug.”

In simpler terms, it is mathematically impossible for one team’s successful digs to exceed the number of attacks made by the opposing team, accounting for kills and errors.

Mathematically, a team can, however, have the same number of digs as the opposing team’s attacks. Achieving this scenario implies that the team successfully dug every spiked and tipped ball throughout the match, a challenging but possible feat.

Additionally, it’s essential to note that a dig is only credited during an attacking play. If a team mishandles the ball, and a player has to dig it out, this instance does not count as a dig in statistical terms.

Digs, being a form of passing, hold significance in passing statistics, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of a team’s performance in receiving and defending against attacks.

In volleyball, pass grades are categorized into four levels:

- Resulting in the attacking team scoring, the “No pass” grade denotes a situation where the pass is ineffective.

- Characterized by teammates facing difficulty in playing the ball, the “Poor pass” grade indicates a suboptimal pass quality.

- Marking a good ball but placing the team out of the system, the “Acceptable pass” grade acknowledges the pass’s adequacy while noting its impact on team positioning.

- Earning the highest accolade, the “Perfect pass” grade is bestowed when a pass not only maintains the team in the system but also facilitates the potential for a counterattack.

What Is the Difference Between a Dig and a Pass?

In the realm of volleyball, a crucial distinction governs the classification of defensive plays: a dig is only acknowledged if the defending player successfully retrieves the ball from the attacking team’s offensive play.

Conversely, if a player digs the ball following mishandling by their own team, it is categorized as a pass rather than a dig. Similarly, if the defending team attempts to block the attacking team’s ball and subsequently makes another touch, it is considered a pass, not a dig.

This principle extends to situations where the attacking team’s player isn’t actively attacking the ball but merely sending it over the net to avoid a four-hit violation.

In such cases, there can be no dig, only a pass.

While players might not be overly concerned about the nuanced difference between a dig and a pass, it holds paramount importance in statistical tracking. Mixing up digs and passes could lead to inaccurate statistics, such as erroneously indicating more digs than the opposing team’s attacks.

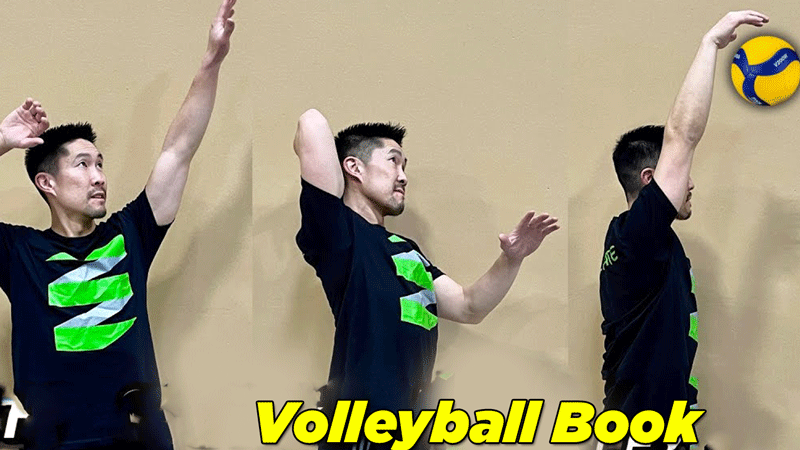

What is the correct way to execute a dig?

On the court, the process of digging involves several rapid steps. While it may initially appear complex and somewhat chaotic when read, with practice, these actions can be honed to a level where the player instinctively knows how to execute a successful dig.

1. Position Yourself Right

In the pursuit of effective digging, the initial crucial step involves achieving proper positioning. As the attacking team executes their play, you and your teammates must be poised and waiting in designated spots. This strategic placement ensures that, regardless of the ball’s trajectory, one of you will be well-positioned to execute a successful dig.

Positioning, in essence, entails a sequence of small steps that lead to optimal placement, with the arms ultimately playing the pivotal role in digging the ball. Reflecting on the broader context of volleyball, it becomes evident that positioning holds paramount importance not only in digs but also in spikes, blocks, and receiving serves.

2. Stay Nimble and Ready to Pounce

Secondly, maintaining agility is crucial; stay light on your feet, low to the floor, with bent knees, and be prepared to move swiftly at a moment’s notice. Adopt the bump position, where forearms come together, ready to receive the ball.

This stance ensures that when you identify the ball’s trajectory, you can seamlessly intercept it.

Given the remarkable speed at which the ball approaches, it’s imperative to be prepared when it arrives. If you remain stiff with your arms at your sides, you won’t have enough time to react to the ball. Being agile and assuming the proper stance enhances your ability to respond effectively to the incoming ball.

3. Predict the Ball’s Trajectory

The third essential step involves closely observing the attacking team’s play and predicting the ball’s landing spot. While initially daunting due to the ball’s rapid movement, your reflexes play a crucial role in this step.

In a split moment, you must anticipate the trajectory, and once you ascertain where the ball will land, adjust your positioning accordingly to efficiently receive it.

Being observant grants you the ability to discern patterns in the attacking team’s plays, allowing you to predict the ball’s landing spot even before it’s hit. Achieving this level of game reading, however, requires experience and keen insight, marking a player as adept and experienced in the sport.

4. Reposition Yourself

Once the anticipated landing spot is identified, the next crucial step is to swiftly move to intercept the ball. Particularly challenging during spikes, where the ball moves at an incredible speed, this requires almost instantaneous repositioning.

Despite the difficulty, when the ball is spiked into your zone, making quick, small adjustments can position you correctly to execute a successful dig.

However, in instances where the ball’s speed leaves no time for bodily adjustments, resorting to diving becomes a necessity.

Diving is an improvisational technique, a last resort where you throw yourself to the spot where the ball will hit, extending one or both of your arms to strike it from the bottom. It becomes a spontaneous maneuver to salvage the play when the rapid pace of the ball prevents conventional adjustments.

5. Strike the Ball

The final and crucial step in the process of digging a ball is the actual execution of the dig. Having correctly predicted the ball’s trajectory and positioned yourself accordingly, the last action is to make contact with the ball.

The optimal technique for digging involves using both arms in the bump position, where forearms come together. This technique provides better ball control and is considered the ideal approach.

However, there are instances where players resort to using just one arm. This usually occurs when a player finds themselves in a suboptimal position, and the speed of the ball demands a quicker response. While using one arm is faster, it sacrifices some ball control.

This decision between using one or both arms is often made on the spot and becomes more intuitive with increased experience on the court.

It is essential to emphasize that, during the striking of the ball, the objective is to pass it to a teammate, enabling them to organize a counterattack. If the ball fails to reach a teammate, the dig is deemed unsuccessful.

Also Read: What Is A Kill In Volleyball? [Guide 2024]